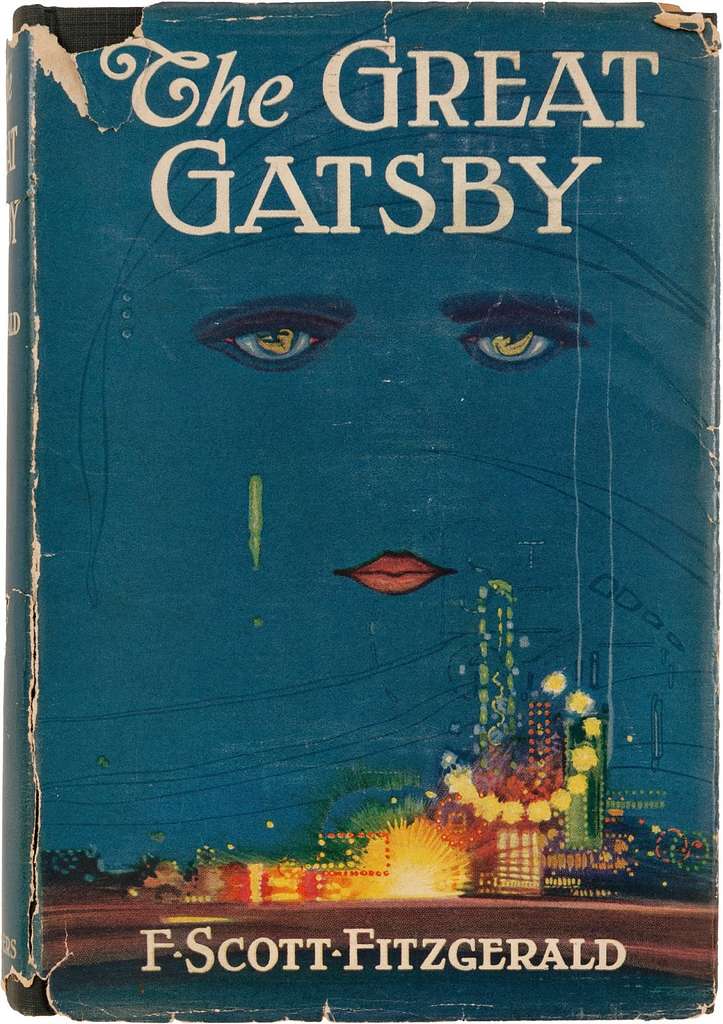

At 100 “The Great Gatsby” is as urgent as ever, old sport

In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s immortal novel, America’s graft and glory are entwined

The Economist | March 14th 2025

HE IS A relative of Kaiser Wilhelm and spied for Germany during the first world war. His dazzling house is actually a boat that creeps along the Long Island shore. He killed a man once; he is “second cousin to the devil”. A quarter of “The Great Gatsby” has passed before, at one of his lavish parties, Jay Gatsby bumps into Nick Carraway, the narrator, and the legend at last enters the action in person.

Gatsby is as much a rumour as a character, a phantom in his own drama—one of the main reasons he has survived for 100 years and counting. Beneath its shimmering surface, or rather because of it, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel raises enduring questions without resolving them. They are as timely now as when it was first published in spring 1925: questions about memory, money and, above all, about America. Its promise and corruption, abundance and menace are facets of the same story.

The short novel is itself a gossamer thing. Not much happens in it. An enigmatic man courts an old flame and is murdered. Another chap has a tawdry affair. Rich people sit around in delicious ennui. The book flopped on publication; H.L. Mencken, an eminent critic, dismissed it as “a glorified anecdote”.

Yet from the 1940s “The Great Gatsby” rose up the American canon and swept across school curriculums (a stage version seems always to be playing somewhere). Its ornate, high-wire language crystallises deep, intractable themes. One is the tragic tango of time. Gatsby is at once in flight from his humble origins and desperate to reprise his most halcyon moment. “Can’t repeat the past?” he cries. “Why of course you can!” These days some people see Western history as a stain, as others yearn to recover lost golden eras: Gatsby’s one-two of rejection and nostalgia writ large.

Next, the issue of money, and related but distinct, the matter of American class. Spouting white-supremacist claptrap and bogus moralising, Tom Buchanan is a cheat and a bully—on whom breeding and background confer a social status and meretricious ease that Gatsby’s brash wealth cannot buy. Gatsby is a champion for every outsider who, pressing their nose against the glass, fears that the system is rigged against them and that grit and hustle can take them only so far.

So Fitzgerald’s is a tale of sex and dough; in other words, of New York. But as he intimates at its close, in a riff about Dutch sailors encountering “the new world”, it is more than that. It is a story of America, the great novel of the country’s entwined glory and heartbreak.

A drumbeat of violence thuds through the prose, such as in the drowning, suicide and other sticky ends to which, Nick casually mentions, some of the guests at Gatsby’s parties would later succumb. Its ethereal elements, the fluttering dresses and deathless devotion, collide with the earthly, brutish and hard (a man’s hand breaking a woman’s nose, a car’s bumper, a gun). At those soirées, “Girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars.” Elsewhere Fitzgerald zooms in on a yucky dollop of shaving foam on a drunkard’s cheekbone and a breast torn off in a wreck.

The ideal and the bruisingly real, the seductive and the sordid, hope and cynicism, beauty and betrayal, and, ultimately, the dream and disappointments of America: Fitzgerald holds these opposites in a magical equipoise. “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?” wondered the bard of another stretch of the eastern seaboard, Bruce Springsteen. That is the mystery at the heart of “The Great Gatsby” and, a century on, it is as urgent as ever, old sport.■

Category: 5 - Back Story columns on culture