Billy the kid: crime and punishment interrupted

Billy the kid: crime and punishment interrupted

A tale of repentance, redemption and reinvention

The Economist | Jun 30th 2016 | LONDON, KENTUCKY

“EVERYBODY can change,” Bill insists; “everybody has the ability to turn their life around and do something good with it.” His own experience, after a youthful spell behind bars, vindicates that optimism: in many ways he is a heartening model of rehabilitation. In jail he realised that “I need to do better than this”; at liberty, he has “done everything I could to do the right thing.” Those who know him best think he has succeeded. He is “a very giving, caring person,” says his pastor, Charles Shelton, who recalls Bill taking in strangers who had broken down on the road. “Just a good man,” Mr Shelton attests. The only wrinkle is the way he gained his freedom.

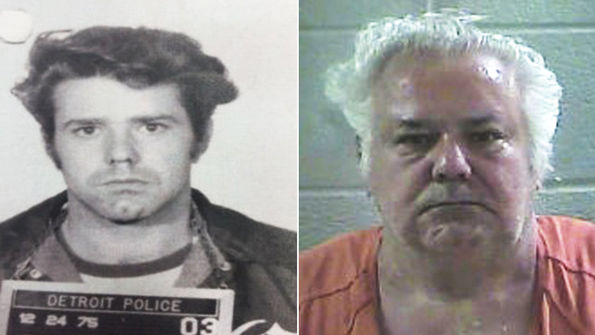

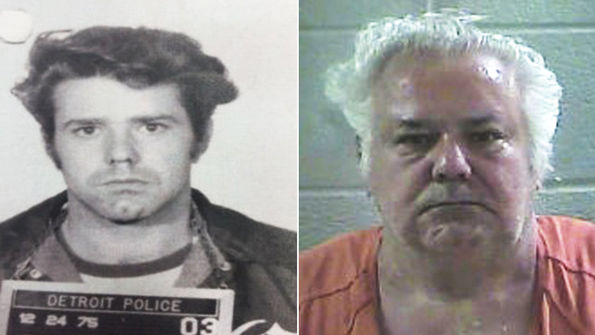

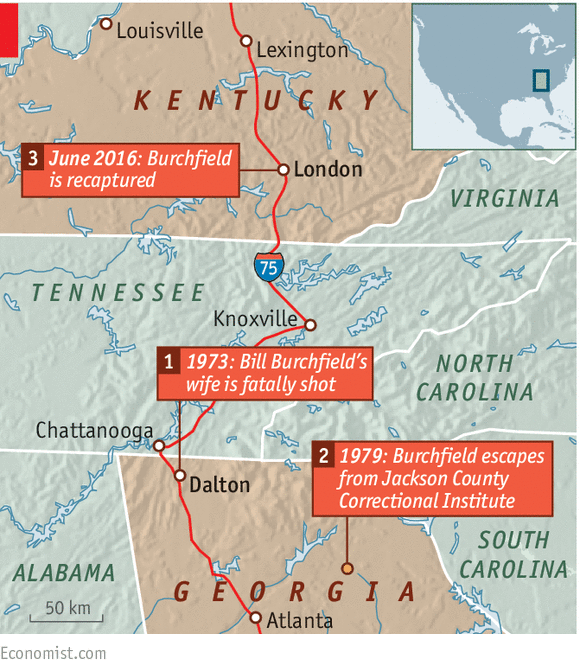

That, and his crime, were a secret he guarded for 37 years until, on the evening of June 15th, two local detectives visited his home on the outskirts of London, a small town in Laurel County, Kentucky, in the foothills of the Appalachian mountains. Bill recognised the men and wasn’t alarmed by their appearance on his doorstep: “I didn’t think nothing about it,” he says, “until they told me what they were there for.” Namely, their hunch that the paunchy, grandfatherly 67-year-old was not, in fact, Harold “Bill” Arnold, as his outward life suggested, but Bill Burchfield, who had escaped from prison in Georgia in 1979. At that point, Mr Arnold/Burchfield recounts, he thought, “Here we go.”

Which of his surnames to use is only the most obvious question raised by this tale of redemption and recapture. Bill’s story—a warped parody of the American ideal of self-invention—also underscores doubts about the purpose of prison, to which he now seems destined to return. Meanwhile the confusion over his name points to deeper mysteries, philosophical rather than legal, concerning the nature of identity and its mutation over time.

Initially he denied being Bill Burchfield, but then the detectives took him into town to be fingerprinted. He followed behind them, obediently driving himself. “It was very strange,” he says in the Laurel County Correctional Facility. Yet, frank in the manner of a man with nothing more to lose, he acknowledges that “in the back of my mind, I expected this to happen.” The fingerprints confirmed that he was Burchfield; he gave up the pretence, and ultimately agreed to be extradited to Georgia.

Prison works

It was in Dalton, Georgia, another town in the Appalachian foothills, that Bill’s wife, Vera Sue, was fatally shot on 5th July 1973. She had two children from a previous relationship, Bill says; according to court records, he was a truck driver with a sixth-grade education and a previous conviction for theft. In his account, it was an accident. He blames himself for having a gun in his hand, but says it went off when she tried to wrestle it away. A bullet hit her in the neck. “I was blessed to have her for a few years,” Bill says, momentarily breaking down—a breach in what, for a man in his bizarre predicament, is impressive composure. Her death was “the most tragic thing that ever happened in my life”. Evidently his metamorphosis did not wipe clean his conscience: the shooting, he says, is “something you live with every day”.

Bill’s version of those events is hard to assess because there wasn’t a trial. He denied the original accusation of murder, then pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of voluntary manslaughter. “I was young and scared,” he says, devastated by his bereavement and advised by his court-appointed lawyers that, if he didn’t cop a plea, he would never be released. (Of the two defence lawyers named in court papers, one has died and the other says he has no recollection of the case.) The decision “was a terrible mistake”, Bill now believes. The judge gave him 15 years’ hard labour.

That rose to 16 years after he escaped—for the first time—from the Jackson County Correctional Institute in 1975; on that occasion he was soon picked up in Detroit. Then, on October 22nd 1979, he fled again, this time from a work detail at the county landfill. The Jackson Herald reported that he asked permission to relieve himself in some bushes, then vanished.

Since he may face fresh charges over the breakout, Bill can’t discuss it. But afterwards, he says, he borrowed a vehicle and drove to California. He slept in the car, then in a cheap motel and took any work he could find. He washed dishes and pumped gas until he landed a job on an oil rig. He had two children. It was a hard life, and when, around 30 years ago, the oil work fell away, he moved back east to London, a quiet town with a picturesque setting and an abundance of churches, and a prosperous one by the hardscrabble standards of eastern Kentucky. It is directly up the interstate from Bill’s old home in Dalton.

Like thousands of Americans who start again in new places, albeit with a twist, he built a different life. He had assumed the identity of a cousin from Georgia, Harold Arnold, who died as a teenager, though informally he retained his first name: a tell-tale clue within his alias that apparently no one clocked. The protracted deceit seems an astonishing exercise in discipline: “That’s a feat in today’s world,” agrees Gilbert Acciardo of the Laurel County sheriff’s office, which collared him. As Bill tells it, though, the striking thing is not how arduous the impersonation was, but—logistically at least—how easy. He applied for a Social Security number in his cousin’s name and got one; nobody ever objected that the real Harold Arnold was dead. He was careful “to stay inside the law”.

Otherwise, fugitive though he was, he lived “like a normal human being. I wasn’t out there trying to duck and dive and hide.” The deceit was “part of my everyday life”. His basic method was to “work hard, and when you get off from work, go home”. He drove trucks, as he had in Georgia; among other businesses he ran a petrol station and café, on a road that winds towards the mountains from the car workshops, farm-equipment dealers and anytown drive-throughs on the edge of London. The café was popular with police and US marshals: they gathered there for coffee and for Bill’s fish lunches on Fridays. He wasn’t shaken by the uniforms—“It wasn’t, ‘Oh my God, they’re a cop’.” Most, he says, were “super-nice people”.

He married twice more and had two more children. His first Kentucky wife died of cancer; Bill is said to have cared for her lovingly, as he did for a half-brother who came to live with him and died recently. (Whether and which of his relatives knew the truth is another subject he is wary of.) He and his most recent wife, Jean, divorced but remained on good terms. She answered the door at his home near the café, and before tearfully closing it described him as “the most kind, the most wonderful man you could ever meet. He helped so many people in the community.”

That estimation seems to be widely shared. When a ghastly crime occurs, it is normal for the suspect’s neighbours to say how mild and considerate he seemed. In this case that sentiment is based on long acquaintance after the offence rather than brief knowledge before it. Sitting beside a fruit stall in his wheelchair, between the café and a little stream, Tim Johnson says that “Bill Arnold is as good a man as I’ve ever met.” Bill, he says, gave him a trailer that he had previously used as a cigarette kiosk: “I never know’d anybody that’d say he’d wronged them.”

By any other name

Mr Johnson and others report that Bill would sometimes give free meals to struggling locals, and that he held Thanksgiving dinners for the indigent. Mr Shelton, the pastor, baptised Bill, who subsequently became a deacon in their church. Bill, he summarises, is “more like a brother to me than a friend”. “I’ve always tried to treat people the way I wanted to be treated,” Bill comments of all the testimonials. “I think my cousin would be proud.”

Still, the affection can’t have been universal: someone had enough of a grudge against him to tip off the authorities in Georgia, though they won’t disclose who and Bill has “no idea”. As a result he may have to serve the ten remaining years of his old sentences, plus any additional punishment for the escape. Contemplating that prospect, he says he considers God’s forgiveness more important than Georgia’s, but hopes that earthly powers may show mercy too. “My health is gone,” he says—he has had several heart attacks, bypass surgery and back problems—“I won’t be around many more years, at the best.” He understands that prisoners can’t simply be allowed to abscond, since “the world is a bad, evil place”, but would like Georgia to say “We don’t want him.”

“Shouldn’t [his] debt be mitigated by the life that he has lived?” asks Jason Kincer, his lawyer. And indeed the idea of returning him to jail, harmless and greying as he is, for something that happened 43 years ago, seems perverse. No one would be safer; he is as rehabilitated as he can be. On the other hand, lots of prisoners wind up inside for one-off misjudgments; many leave behind dependents and disregarded good deeds, just as Bill may do now. His case is extraordinary, but the quirks in the penitential system it highlights are routine.

His neighbours seem unequivocal. A petition calling him “a true and faithful friend of all citizens of Laurel County” and requesting his release has garnered hundreds of signatures. At the same time there is the disorientation of learning that he is not quite who they thought he was—another acute instance of a familiar syndrome. “I never had a hint of anything like that,” says Mr Shelton, struggling over which of Bill’s surnames to use. “It’s a different person they’re incarcerating”, he thinks. In all their years of intimacy, Mr Johnson is sure that “at some point he would have mentioned something that big”. He thought the whole farrago was a practical joke, or a mistake, or a miscarriage of justice. “If he is the person they say he is, he is reformed,” Mr Johnson says. “He’s still Bill Arnold to me.”

As perhaps he should be. The law’s view is clear and inevitable, but in other ways Bill’s identity is fuzzy. After all, he has been Bill Arnold for longer than he was ever Bill Burchfield, an incarnation he now believes he has sloughed off, as people often feel of their unrecognisable, younger selves. “You are who people know you to be,” Bill figures. “I’m Bill Arnold, I’m not Billy Burchfield. Maybe not on paper, but in here,” he says, gesturing to his dicky heart through his prison smock. “That’s who I am today, and who I will always be.” If somehow he does scrape through this, there is something he wants to do: change his name officially, eschew Bill Burchfield for ever and live as Bill Arnold, in peace.