Five Best: History in fiction

Five Best: A.D. Miller on Historical Events in Fiction

The Wall Street Journal | April 17th 2020

From the author, most recently, of ‘Independence Square.’

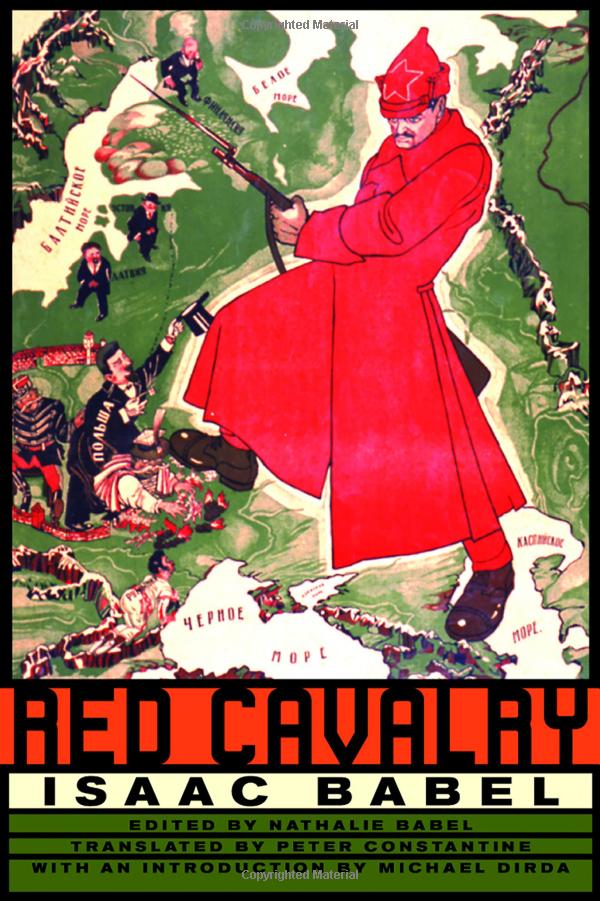

Red Cavalry

By Isaac Babel, translated from the Russian by David McDuff (2005)

1. In 1920, while serving as a correspondent in the Polish-Soviet War, Isaac Babel galloped into battle with Cossack cavalrymen—a daunting commission for a bespectacled Jewish writer. “Remember,” he told himself in his diary, “describe.” And he did: The stories he set in this now-forgotten campaign ambush the reader with their piercing, luminous details. The narrator, Lyutov, kills an old woman’s goose to win his comrades’ approval; afterward, sleeping beside them, his “heart, stained crimson with murder, squeaked and overflowed.” A mortally wounded soldier beseeches Lyutov to finish him off, but he is unable to; instead, he finds himself “begging fate for the simplest of abilities—the ability to kill a man.” With all their horror and pity, these masterly tales made Babel a literary star, a status that, under Stalin, carried risks. Long before he was shot in 1940, he had stopped publishing his work, insouciantly describing himself as a “master of the genre of silence.” In the literary museum in Odessa, Babel’s hometown and a place I love, a pair of his wire spectacles is pinned hauntingly to the wall.

The Quiet American

By Graham Greene (1955)

Graham Greene turned his years in Vietnam in the early 1950s into this short, searing exploration of the relative dangers of cynicism and idealism. Pyle, the American of the title, “had a way of staring hard at a girl as though he hadn’t seen one before and then blushing,” yet for all his seeming innocence, he causes many deaths, and winds up stabbed with a rusty bayonet. In moments of crisis, the novel asks, if and when, like its characters, you have blood on your shoes, can you avoid getting involved? Nobody is better than Greene at conveying the ruinous stimulations and gallows jollity of expat life: days “punctuated by those quick reports that might be car-exhausts or might be grenades,” the sense that anything goes and nothing matters, until it does. As ever in his world, consequences are unintended and motives mixed—as opaque as the sigh of a colonial policeman on a balmy night “that might have represented his weariness with Saigon, with the heat, or with the whole human condition.”

Bring Up the Bodies

By Hilary Mantel (2012)

He has to do it. This Thomas Cromwell—a figure so vivid that, like Shakespeare’s Richard III, he eclipses all other versions—has little choice but to destroy Anne Boleyn, his ally until she isn’t. At least, in a novel that makes a Tudor minister seem like our contemporary, that is how it feels. With their factionalism, foreign meddling and class resentments, the book’s politics chime with today’s, albeit with an added emphasis on royal lust and the constant risk of execution. When Henry VIII briefly seems to have died, Cromwell is torn between an impulse to seize control and the urge to flee abroad. He is all in, all the time. “If he had a grievance against you,” Hilary Mantel writes, “you wouldn’t like to meet him at the dark of the moon.” But he isn’t cruel; he can even be kind. He is just supremely realistic. The king wants to be rid of his wife, so, naturally, Cromwell supplies a pretext, luring his targets into boasts that become damning evidence. “I take it back,” one stooge says of a confession he believes he has made, but actually hasn’t. “I don’t think so,” Cromwell tells him.

Austerlitz

By W.G. Sebald (Translated by Anthea Bell, 2001)

So overwhelming is the Holocaust, W.G. Sebald thought, that it can only be approached from an angle. In “Austerlitz,” which draws on “three-and-a-half” real people, the German author came as close as he ever did to a subject that shadows his whole oeuvre. Of all his original, mesmeric books, this is also the nearest he got to writing a conventional novel. As a teenager in Britain in 1949, Jacques Austerlitz learns that he came to the country when he was 5; decades later, he returns to his birthplace, Prague. Striving to recollect his mother, he “cannot make out her face” but manages to summon a heartbreaking memory in which “I see the scarf slip from her right shoulder as she lays her hand on my forehead.” What Sebald mourns here is not so much violence as loss. His text is punctuated by uncanny images (a child in a pageboy costume, architectural plans, a stamp), relics of a past that is both real and invented, lost and always with us. He writes in long, looping sentences that seem forever to be turning back on themselves, attempting, in miniature, what his book tries to do overall: reverse time, and thereby resurrect the dead.

Hadji Murad

By Leo Tolstoy (Translated by Aylmer Maude, 1912)

Leo Tolstoy tried to give up writing fiction, which in his later, ascetic years he regarded as a shameful vanity. But he couldn’t. “Hadji Murad,” published after his death, squeezes all the life that teemed in his longer novels into 150 limpid pages. We meet rivalrous courtiers, bereaved mothers, unfaithful wives, a coachman drawing up at the Winter Palace in a velvet cap—all instantly brought to life with the wondrous gift for character that is the essence of Tolstoy’s genius. The story is based in part on events that he witnessed firsthand while soldiering in the Caucasus in the 1850s. Hadji Murad, a fearsome but honorable rebel chieftain, goes over to the Russians; later he escapes to rescue his family, whom his enemy Shamil has captured. Facing impossible choices that nevertheless must be made, Hadji Murad exemplifies what it is to be buffeted by history. Yet with his limp, his turban and his childhood memory of a dog licking his face, he is also human. Morally, his real antagonist is not Shamil but the cruel and conceited czar who, in faraway St Petersburg, wonders, “what would Russia do without me?”