Moses in the Ozarks: the parable of Italians in Arkansas

Moses in the Ozarks: The parable of Italians in the South

Migration, race, a charismatic priest and lots of cannelloni

The Economist | May 27th 2017 LAKE VILLAGE AND TONTITOWN, ARKANSAS

THE cellar is flooded and Chris Ranalli worries about snakes. From the safety of the back door, he points out the sturdy walls—two feet thick, as if to withstand Mediterranean earthquakes—and the elegantly vaulted ceilings. “They lived in the top two storeys and made wine in the basement,” explains Mr Ranalli, who now tends the 100-year-old vineyard adjacent to the house. The view from the road is anomalous: framed by Catawba trees, the façade combines northern Italian architecture and Ozark stone, seeming to belong as much to the Apennines as Arkansas.

This house tells a story that is both familiar and extraordinary, as the exploits of immigrants to America tend to be. It is a tale of struggle and success, of awful but commonplace suffering, villainy and heroes, including a dauntless priest who, like a latter-day Moses, led his flock to a new life in the mountains. It epitomises the variety behind the strip-mall, fast-food sameness of small-town America, but also the loss that can be a bittersweet corollary of progress. And, like the house itself—standing but decrepit—it is only half-remembered, the sort of amnesia that helps to explain attitudes to immigration today.

The house was built a century ago by Adriano Morsani, a stonemason from central Italy. He is captured in old photos as a moustachioed patriarch, beside a wife in a smart hat and children squinting into the sun. But the story is quintessentially American. It begins on the floodplain of the Mississippi, close to Arkansas’s border with Louisiana, in the turmoil after the civil war.

Today the fields enclosed by the Mississippi and the horseshoe of Lake Chicot are punctuated by grain bins, plus a few labourers’ dwellings guarded by bored dogs. The lakeshore is lined with idyllic homes with pretty jetties and private boats. A hundred years ago, when this was still the Sunnyside plantation, the villas had not been built; nor had the suspension bridge that, near one of the narrow openings between lake and river, now links Arkansas with Mississippi. The water that almost encircles the fantastically fertile, sandy-loam soil made it a natural prison camp.

In 1861 Sunnyside was among the largest, richest plantations in Arkansas. It was owned by Elisha Worthington, who scandalised white society by recognising two children he fathered by a slave. After the war, as cotton prices plunged, it belonged to John Calhoun, namesake and descendant of the southern ideologue, and then to Austin Corbin: a robber-baron financier and railroad speculator, who, as a founding member of the American Society for the Suppression of the Jews, barred them from the hotel he built on Coney Island. Corbin installed a steamboat and a small railway, but, like many southern landowners, struggled to find labour. He experimented with convicts, then hit on an alternative: Italians.

The levee wasn’t dry

Like many people-traffickers, then and now, Corbin had a man on the inside. His was Don Emanuele Ruspoli, the mayor of Rome, who recruited workers from Le Marche, Emilia-Romagna and the Veneto. The first batch—98 families—sailed from Genoa on the Chateau Yquem, a reputedly rancid steamship that arrived in New Orleans in November 1895. The families clutched contracts showing that each had bought a tract of land, on credit to be repaid in cotton crops. After a four-day journey up the river to Sunnyside, they quickly realised that they had been misled.

“The first year, 125 people died,” says Libby Borgognoni, a magnetic 81-year-old whose in-laws came over on the Chateau Yquem (her grandfather arrived later, after drawing the shortest straw of his family’s six sons). Hot, humid and swarming with mosquitoes, Sunnyside was fecund but deadly. Today you can drive on a gravel road on top of the levee between the fields and the Mississippi, the wide, eddying river and glacial tugboats on one side, cotton on the other, red-winged blackbirds darting between them. When the Italians arrived, the barrier was lower, and floods were common. The drinking water was filthy; yellow fever and malaria were rife. Climbing into his hunting truck, Tom Fava, another local Italian-American, helps to find the disused cemetery where the victims lie. It is hard by Whiskey Chute, a stream named after a cargo of whiskey scuttled by brigands during a fire-fight.

Many of the millions of Italians who moved to America in that period, mostly to industrial cities in the north, suffered. But rarely like this. Heat and disease were the worst of it, but Corbin’s terms were onerous too. The Italians spoke little English; many were illiterate. But they could see that the land had been wildly overpriced. And while many were farmers, Mrs Borgognoni admits “they knew zip about cotton”. Anti-Italian and anti-Catholic prejudice swirled: 11 Italians had been lynched in New Orleans in 1891. Mrs Borgognoni recalls that, well into the 1930s, locals would roll the car windows down and holler “Dago!” at Italian children.

In 1896, six months after the first Italians landed, Corbin died in a buggy accident near his exotic hunting lodge in New Hampshire (he was said to have startled the horses by opening a parasol). Still, a second boatload left Genoa for Ellis Island in December. Another Italian also made the trip from New York that year. Pietro Bandini grew up in Forli, joined the Jesuits and was sent as a missionary to Montana’s Native Americans. Later he moved to New York to minister to put-upon Italians. For those at Sunnyside, he was a redeemer.

Bandini protested against the conditions. Legend tells that, when he was rebuffed, he told his acolytes to wait while he scouted a better environment. During his absence he arranged to buy land in the prairies west of Springdale, near what was then Indian Territory and is now Oklahoma. In early 1898, 40 families junked their contracts and followed him northwards.

Precisely how they got from the Delta to the Ozarks, then a more arduous journey than it is today, is a matter of dispute. “They walked,” insists Charlotte Piazza, whose Italian-born father-in-law was in the original caravan. Some brought livestock, paying their way by doing odd jobs at Catholic churches along the route and hunting for food. Rebecca Howard, a historian at Lone Star College in Texas, thinks some travelled part of the way by train. Ms Howard’s great-great grandmother, Rosa Pianalto, buried a child at sea during the crossing on the Chateau Yquem and her husband shortly afterwards. She was remarried and pregnant for the Sunnyside exodus.

Towards the promised land

They would have set out, initially, across the big-skied plain of southern Arkansas. The road that crosses it today runs through Dermott, a hamlet with giant pecan and fireworks stores and an outsize “Gospel Singing Shed”, then skirts the site of an internment camp for Japanese-Americans and the state’s death-row prison. They would have crossed the brown Arkansas river at still-skyscraperless Little Rock, before turning west into its valley, where the land begins to undulate. Some Cherokee, Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians had followed that route on the “Trail of Tears”; it passes through forests and pastures and beside timber yards, lakes and creeks. They might have gulped as they approached Fort Smith, now a picturesque tourist town, then a frontier outpost renowned for a subterranean prison known as “hell on the border”.

The railway from Van Buren to Springdale, which some probably rode on, is now used for tourist excursions, plunging into the Ozarks through mountain villages that grew up around what was formerly a commercial line. The chug across the Boston Mountains, the most rugged section of the Ozarks, with sheer cliffs and elevated trestles, must have seemed a dizzying lunge into another unknown future. At the same time, says Mr Ranalli, the winemaker, the cooler, higher landscape and temperate plateaus “felt like coming home”.

A list of the pioneers is etched on a monument outside the town hall of Tontitown, the name they chose in honour of Henri de Tonti, a 17th-century Italian explorer. There were fewer mosquitoes but, to begin with, life remained hard. They lived in abandoned log cabins while they cleared the land, stuffing the cracks with linen to keep out drafts; Morsani, the stonemason, his brother and their five children shared a barn with several other families. They survived on pasta, polenta and wild rabbits. The men went to work on railways or in mines until the crops came in. Women took jobs as housekeepers in Eureka Springs. The locals were hostile: the Italians’ first church was set alight, reportedly with Bandini inside. He survived to warn the barrackers that his compatriots were handy with firearms. (The second church was lost to a tornado.)

Tontitown prospered, largely through his ingenuity. “It was almost like he was a saint,” says Mr Ranalli of Bandini’s reputation. He was the new town’s teacher, bandleader and first mayor, as well as its priest. He negotiated to bring in a railway spur. He imported vines: the soil is poorer than in the Delta, Mr Ranalli says, but the drainage better suited to grapes. He was honoured by the pope and Italy’s queen mother.

When Edmondo Mayor des Planches, the Italian ambassador, visited in 1905, Tontitown was thriving. Its residents were “happy, contented, prosperous”, des Planches wrote. “Italy, the place of their birth, was their mother, while America was their wife. They have reverence for the former, but love for the latter.” Photos in Tontitown’s historical museum capture his welcome, Stars-and-Stripes and Italian tricolours waving as he is escorted along dirt roads by locals dressed to the nines.

Bandini died in 1917, but Tontitown’s success outlived him. During prohibition, says Mrs Piazza, one of the museum’s founders, people hid wine barrels in basements and vineyards. The bars on the windows of the Morsanis’ cellar were added to comply with post-repeal rules, Mr Ranalli says. When he was a child, in the 1960s, there were still a few old-timers who spoke only Italian. They had realised the American dream, and their own: from poverty in Italy, via devastation in the Delta, to a life in which many families lived on streets that bore their names—Morsani and Ranalli Avenues, Piazza and Pianalto Roads.

That, for its citizens, is the moral of Tontitown’s story. Their pride is justified. But the travails of the Italians in Arkansas resonate in darker ways, too.

Ambassador des Planches also visited Sunnyside on his southern jaunt. The scene was much less salubrious. Three cotton factors from Mississippi leased the plantation from Corbin’s heirs, using illegal methods to import more Italians. These transplants found themselves trapped by debts: for the cost of travel (their own to America and their cotton’s to market); for ginning fees and doctor’s fees; for the necessities they were obliged to buy at exorbitant prices from the company store, all accruing interest at 10%. Some fled; some who were caught, says Mrs Borgognoni, “were taken back by the sheriff in chains”.

Over the river, across the lake

The ambassador complained, and in 1907 the Department of Justice dispatched Mary Grace Quackenbos, an intrepid investigator. Leroy Percy, one of the proprietors, tried to subdue her with both southern gallantry and bullying. Her papers were stolen from her hotel room. An assistant was given three months on a chain gang for trespassing. Nevertheless Quackenbos recommended charges of peonage, or illegal debt servitude. They were never pursued: it helped that Percy had joined Theodore Roosevelt for the famous hunt on which the president inspired the Teddy Bear by declining to kill one. (Percy wound up in the Senate, where he served on an immigration commission.)

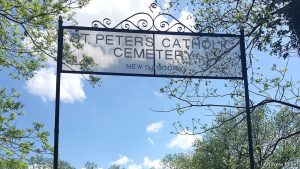

Italian migration to the region dried up, and many of the Sunnyside families dispersed across the Delta, joining small Italian communities that had sprung up on either side of the river, along the Gulf coast, down in Louisiana’s sugar-cane territory and up to Tennessee. Clarksdale, Friars Point, Indianola: their destinations evoke a better-known Delta culture, the blues lore of Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson and B.B. King. Across the river from the plantation, in the part of Greenville known as Little Italy, there is still an Italian club, where members gather to play bocce in pits overlooked by miniature bleachers. On the Arkansas side, at what was once New Gascony, an overgrown Catholic cemetery lies at the end of a dusty track, surrounded by soyabean and cornfields (see picture). All that is left of the flood-ravaged settlement, says a farmer, are a few houses beyond the bayou. The fading Fratesi and Mancini headstones stand like hieroglyphs of a lost civilisation.

Some Sunnysiders, however, simply hopped across the water to Lake Village—today a seemingly typical Delta town, wedged between the nondescript highway and Lake Chicot and bisected by a railway track, beside which squats a cotton gin. Our Lady of the Lake church, and the museum Mrs Borgognoni oversees in its old rectory, reveal its nuances. All the Italian locals once made prosciutto, lonza and salsiccia, she remembers; “church was the biggest thing in the world.” As a child she picked possum grapes in the sloughs and levees to make wine in the cellar of her double-shotgun house. Squirrels were cooked in fornos, or brick ovens. There was a hog roast on the fourth of July and a celebratory spaghetti dinner in March. People played accordions and mandolins, which some think contributed to the blues.

Some Sunnysiders, however, simply hopped across the water to Lake Village—today a seemingly typical Delta town, wedged between the nondescript highway and Lake Chicot and bisected by a railway track, beside which squats a cotton gin. Our Lady of the Lake church, and the museum Mrs Borgognoni oversees in its old rectory, reveal its nuances. All the Italian locals once made prosciutto, lonza and salsiccia, she remembers; “church was the biggest thing in the world.” As a child she picked possum grapes in the sloughs and levees to make wine in the cellar of her double-shotgun house. Squirrels were cooked in fornos, or brick ovens. There was a hog roast on the fourth of July and a celebratory spaghetti dinner in March. People played accordions and mandolins, which some think contributed to the blues.

If the cultures of Italians and blacks in the Delta overlap, so did their experiences. “We ate together, we played together, we worked in the field together, we sang together,” says Mrs Borgognoni. “It was a different world.” Paul Canonici, a former priest and author of “Delta Italians”, a charming collage of family histories, remembers, as a child, peering through the windows of a black church at ecstatic worshippers, and watching black baptisms in the bayou. (In the mid-1920s Klansmen besieged his family home in Boyle, Mississippi, shooting the dog.) Italians, after all, were a marginal solution to the problem of labour in the inhumane conditions of the Deep South. Not just during slavery, but in the brutal ruses deployed after emancipation, from convict-leasing to the debt-trap of sharecropping, most victims were black.

The Italians’ story, in fact, is a sort of shadow version of African-Americans’, the hardship milder and the ending sweeter. That they escaped the prejudice they first aroused was in part because their skin was acceptably white. As Ms Howard, the historian with Tontitown roots, notes, they could enlist external allies—the Catholic church, even the Italian government—that their black neighbours lacked. The Italians, in truth, are a blip in the grim saga of plantation agriculture, if an enlightening one.

If the story of the Morsani house shows that aspects of slavery lingered on, it is also a reminder that what is often thought of as a modern-day kind—based on debt and intimidation—is far from new. And it discloses the mechanism by which some such ordeals come, selectively and misleadingly, to be redescribed as triumphs.

Consider that church-burning in Tontitown. In early accounts it seems that bigoted white locals were responsible. Later, after the Italians were embraced, the culprits changed; now they were Native Americans, who had ridden over from Indian Territory. Through such collective editing, a small part of America’s jagged prehistory is sealed and separated from the trials of immigrants today. Always known to be patriotic and thrifty, the Italians, in this retelling, were different. It isn’t only them. Along with corn bins, cotton gins and Baptist churches, the Arkansas plains, like much of rural America, are littered with places that hint at a hazy cosmopolitan past: Moscow, Dumas, Hamburg.

Forgive and forget

“Have they forgotten how we got here?” asks Paul Colvin, Tontitown’s mayor, of today’s xenophobes. Some people have. Mr Colvin, the first mayor with no Italian connection, himself personifies a wider change, at once routine in immigrant communities and poignant. Even as they cooked the old recipes, the settlers hurried to assimilate, learning English and signing up for military duty. Their descendants married americanos and moved away. Each generation remembers less. Meanwhile, says Mr Colvin, “small towns are getting swallowed by the big towns”, as Walmart and other large employers turn places like Tontitown into dormitory suburbs. Land prices are rising; people are selling up, outsiders replacing them.

Tontitown still holds an annual grape festival, which once marked the grape harvest and by tradition includes a feast of the signature dish, spaghetti and fried chicken. But Mr Ranalli’s is the only commercial vineyard left. “There’s very few full-blooded Italians that still live in this town,” he says. Not many people care about their heritage any more, agrees his daughter Heather, who runs a winery that sells his fine wine. “It’s dying out, and that’s the truth,” says Mrs Piazza, glumly.

Down in Lake Village, says Mr Fava, the good Samaritan with the hunting truck, “the guys who were slaves are now the farmers.” Much of what was once Sunnyside is now owned by Italian-Americans, as are many of the posh homes on the lake, with their fleet of ride-on lawnmowers, as families return to the land from which their forebears fled. As often happened in distant enclaves in pre-internet days, the Italianness ossified—the dialect baffling actual Italians when they interacted with Lake Villagers—then withered, like Tontitown’s. The brick ovens and wine cellars are gone. Much of the old cemetery was ploughed over, the gravestones and crosses allegedly tossed into Whiskey Chute among the half-submerged cypress trees and nesting egrets. The priest at Our Lady of the Lake is a genial Nigerian missionary, Theo Okpara. Does he speak the language? “Nada,” replies Father Okpara, who ministers to more Hispanics than Italians.

Like the shell of the Morsani house, though, some traces remain. Regina’s lakeside pasta shop continues to sell old-style muffalettas, cannelloni and parmigiana, as well as homemade pasta—”real thin, the way you like ’em”, says a non-Italian customer. And Mrs Borgognoni still recalls the songs she learned, aged six, picking cotton beside her grandmother. Her life had been hard, but, says her granddaughter, “when she was happy she would lift her skirt and dance the saltarello.”

Like the shell of the Morsani house, though, some traces remain. Regina’s lakeside pasta shop continues to sell old-style muffalettas, cannelloni and parmigiana, as well as homemade pasta—”real thin, the way you like ’em”, says a non-Italian customer. And Mrs Borgognoni still recalls the songs she learned, aged six, picking cotton beside her grandmother. Her life had been hard, but, says her granddaughter, “when she was happy she would lift her skirt and dance the saltarello.”

One of the songs, Mrs Borgognoni says, is about a young Italian soldier whose wife dies when he is away on duty; he returns to kiss her for a final time. The tune is sad but beautiful. She closes her eyes and sings.

Category: 3 - America