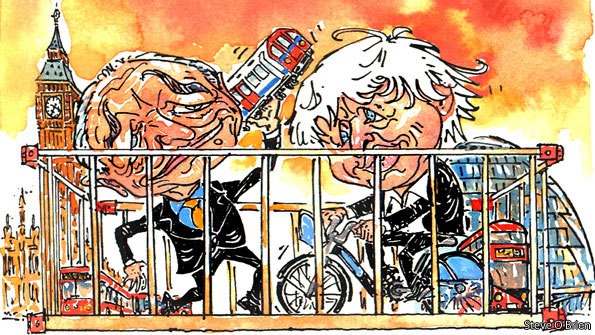

Send out the clowns: London’s mayoral election of 2008

Send out the clowns

The lesson of London’s funny but sad mayoral election

The Economist | April 17th 2008

IN POLITICS, jokes can be serious. A skilful rhetorician—such as William Hague, the shadow foreign secretary—can use humour collusively, recruiting his audience via their laughter. Boris Johnson MP makes lots of jokes; many are funny, and such is his aura of shambolic wit that audiences titter even at the duds. But they are not really purposeful. They are just jokes.

Mr Johnson is the Conservatives’ candidate in London’s tight mayoral election on May 1st. Along with the gags, his oratorical style combines arcane vocabulary and distracted amateurism (“he’s fumbling all over the place,” Arnold Schwarzenegger once commented). The whimsy is coherent enough, however, to have repeatedly if inadvertently caused offence—to London’s ethnic minorities, among others; they have been only partly comforted by Mr Johnson’s apologies and advertisement of his cosmopolitan descent, from a Turk and, reputedly, a Circassian slave.

But those indiscretions are not the main reason to doubt that he is the right man to run London. The main reason is that before deciding, after much equivocation, to stand, Mr Johnson had neither evinced much interest in London nor properly run anything. True, he was editor of the Spectator, a weekly magazine; but rigorous administration is not the trait for which his tenure is most remembered. He is propounding some sensible policies on crime, but for much of the campaign he has been aloof, relying on his already high profile to work for him by proxy: “Boris” was the candidate rather than the actual Boris. His Tory handlers say that, if he is elected, a team of crack managers will help to govern London and govern him: a dubious reassurance, especially since no one knows who they would be.

So the incumbent, Ken Livingstone, ought to clean up. On his watch London has become an even more diverse and magnificent city. That has little to do with Mr Livingstone, but he has made some useful marginal contributions. He bravely introduced a charge to drive into central London; he has improved the city’s buses; he oversaw a revamp of Trafalgar Square. Following a similar ideological trajectory to Labour, the party that he nominally represents, despite his professed socialism “Red Ken” has, as mayor, encouraged developers and championed the City.

Weighing against this record is the mayor’s own problematic personality. The problem is not his taste for mid-morning whisky, his complicated personal life (Mr Johnson’s is also colourful) or his enthusiasm for newts. It is that Mr Livingstone is a megalomaniac. For all his long involvement in local government—he was leader of the Greater London Council until, not unrelatedly, Margaret Thatcher abolished it—ruling London was never Mr Livingstone’s main ambition either. He wanted to be prime minister (at least), and it shows. He has used his consolation job to cultivate Latin American autocrats and fanatical Islamists; when the conversation turns to global affairs, he can sound like one of those sane-seeming people who suddenly claim to have been abducted by aliens. His apologists say these pseudo-radical antics don’t matter: forget the agitprop, they say, focus on the buses. But they do matter, and the symbolism will be even more important in the run-up to the London Olympics.

The absurd freelance diplomacy is not the only hint of megalomania that makes a third Livingstone term look undesirable (he originally said he would seek only one). What often happens to long-serving incumbents, even those who are not confirmed megalomaniacs, has happened to him. His administration has become opaque and detached. He has tolerated and defended dodgy practices among his acolytes, and seems to have used city resources for his own political ends. He is vindictive and insulting to anyone who disagrees with him.

Democracy usually involves choosing the lesser of two disappointments. But in this case the choice is especially disappointing. (The third main candidate is Brian Paddick, a sometime Liberal Democrat and former policeman who made his name with an experimental approach to drugs policing. He is earnest and personable but has no chance of winning.) Alongside the headline quandary—Ken or Boris?—Londoners are pondering another: why are the candidates so badly flawed?

Reductio ad absurdum

One answer—the wrong one—is that they are the candidates the job deserves. The role is weaker than, say, that of the mayor of New York, but it is still the most important directly elected office in Britain. The mayor is compensated for the narrow range of his powers by having few checks on those he does wield (mostly over transport and planning, and to a lesser extent policing).

The real explanation is an historical quirk. When the post was established in 2000, irreverent Londoners used the inaugural vote to cock a snook at Tony Blair, then in his imperial pomp. They elected Mr Livingstone, whose cheeky petulance and nasal whine appeal to some voters as ugly men appeal to some women, and who was loathed by most of the Labour Party even before he stood against its official candidate. To dislodge him, the Tories felt they had to field another first-name-only politician. Even more than most mayoralties, London’s has thus become reserved for mavericks and celebrities.

Therein lies the real lesson of the mayoral circus. So exotic is the race that extrapolating predictions about the next general election from the result will probably be unwise (though if Mr Johnson wins, and then gaffes or flops, the Tories will certainly be wounded, which is why, until recently at least, some of them thought a noble defeat might be preferable). The lesson instead concerns the direction in which all the parties are collectively travelling. In a post-ideological era, everyone now agrees, politics is dominated by personality. In London that proposition has been tested—to destruction. It has been a joke, in other words, with a serious point.

Category: 4 - Bagehot columns on politics