The art of football

When drama and beauty turn the World Cup into art

Heroes, villains, creativity, human frailty: five World Cup moments when art and sport merged

The Economist | June 9th 2018

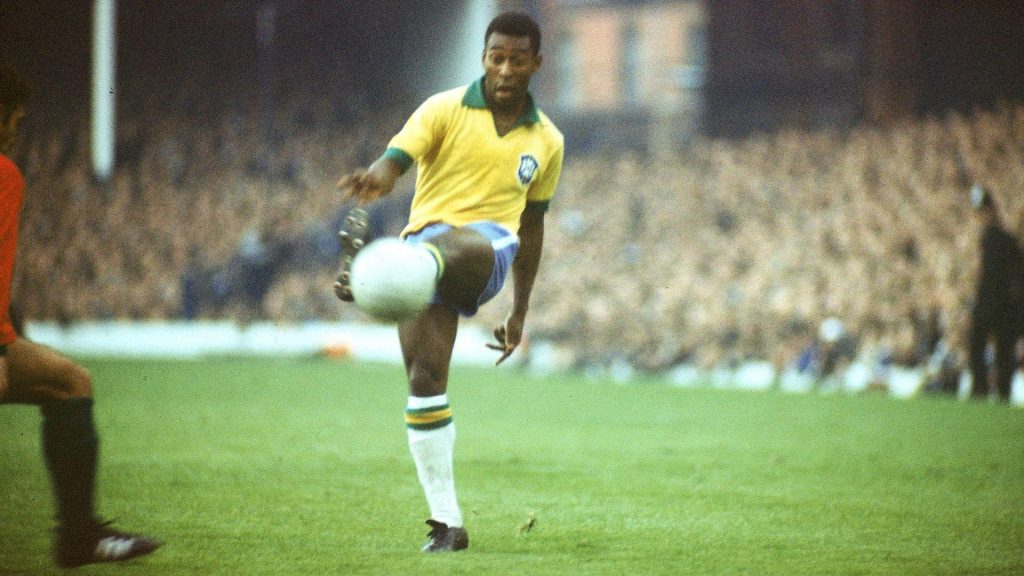

PELÉ was nine years old when he first saw his father cry. It was 1950, the year of the Maracanazo—Brazil’s devastating loss to Uruguay, at the Maracanã stadium in Rio, which cost the team the World Cup. The child promised his father that he would avenge the defeat. When the two countries next met in the tournament, in the semi-final of 1970, Pelé was playing. With the scores tied at 1-1, he chased a pass deep into Uruguay’s half. The goalkeeper rushed from his line. Their foot race was also the climax of a story, or rather several: the story of the game, of Pelé’s career, of his country’s recovery from the Maracanazo.

With its mortifications and sense of worldwide communion, the World Cup—which begins on June 14th—is a kind of global religion. It is a form of soft diplomacy and a safe outlet for nationalism. For many fans, it is a potent quadrennial madeleine, each tournament summoning memories of previous ones, the lost friends with whom they were watched, past selves. Sometimes the football itself can be cagey and boring. But, especially on its biggest stage and canvas, sometimes football is art. Individual moves can be balletic, a team’s routines exquisitely choreographed. Grand narratives unfold and crescendo, tragedies and unlikely triumphs that feature heroes, villains and occasionally players who contrive to be both.

1. Darkness to light. Redemption is one of the fundamental themes of art and literature, from the Bible to the “Odyssey”, from Raskolnikov’s rebirth in “Crime and Punishment” to Rick’s late-breaking idealism in “Casablanca”. In such stories the good and bad that vie in people are heightened and set in conflict. Rarely have a character’s base and noble traits collided as they did at the World Cup of 1986, in which Diego Maradona ascended from infamy to sublimity in a single game.

Not just any game. In 1982 Britain defeated Argentina in a war over the Falkland Islands. Four years later, having emerged from a military dictatorship, Argentina faced England in a quarter-final in Mexico. “We were defending our flag, the dead kids, the survivors,” Maradona, the team’s captain, said later. In the space of four minutes he scored the most scandalous goal in history and the finest. First he surreptitiously punched the ball into the net (the “hand of God”, he called it afterwards). For the second goal, he seemed to function on a different plane to the hapless Englishmen. He pirouetted away from two defenders, ran half the length of the pitch, rounded the keeper and guided the ball home. Argentina won the game and, redemptively, the cup.

Before and afterwards, Maradona’s life was chequered. He grew up in poverty; later he failed drug tests and ballooned. But, as he said in a memoir, “Nobody anywhere is ever going to forget those two goals I scored against the English.” Together they form a diptych as dramatic as Scrooge’s enlightenment or Darth Vader’s conversion. The first “was like stealing from a thief”. As for the second: “It is possible that a more beautiful goal has been scored…but I doubt it.”

2. Present at the creation. Greatness in sport, as in art, often comes from unseen, grinding effort. But sometimes it arises from sheer inspiration—a wind awakening a coal to brightness, as Percy Bysshe Shelley put it, or the “flash in the brain” that Johan Cruyff said he experienced at the World Cup in Germany in 1974.

Cruyff was a master of flicks, feints, impudent shots and passes that described arcing lines of beauty. But it was his improvisation in a match against Sweden that made him immortal. By his own account, he had not practised what he did upon receiving the ball near the corner flag, a Swedish defender in close attendance. Cruyff appeared to be heading away from the goal, until, in a quicksilver feat of dexterity and imagination, he tucked the ball behind him, swivelled and set off in the other direction. For an instant he seemed to be running in both directions at once.

The “Cruyff turn” has since been attempted by players everywhere. Seeing it for the first time was akin to hearing the impossible, unscripted E-flat sung by Maria Callas at the end of “Aida” in Mexico City, or watching Michael Jackson unveil his moonwalk. When Cruyff died, one of the best tributes came from Jan Olsson, the defender he bamboozled. “I loved everything about this moment,” Mr Olsson said. “I am very proud to have been there.”

3. Dust to dust. In 2009 the artist Mark Wallinger curated an exhibition on the theme of boundaries and doubts. It contained trompe l’oeil paintings, artificial flowers and a fake Tardis, or perhaps a real one. Mr Wallinger called the show “The Russian Linesman.”

Fittingly, the linesman to whom that name referred was not actually Russian. His name was Tofiq Bahramov and he was from Azerbaijan. Bahramov officiated at the World Cup final of 1966, played between England and West Germany at Wembley Stadium in London. With the scores level in extra time, a shot by Geoff Hurst, England’s striker, rattled the crossbar and bounced down over the goal line. Or perhaps it didn’t: the German players claimed to have seen chalk dust, indicating that the ball hit the line and thus that the goal should not be given. The referee jogged across to consult Bahramov, who briskly nodded an affirmative.

England won 4-2. English fans mostly remember the fourth goal, scored in the final seconds as the joyous crowd spilled onto the pitch. But it is the third that is a work of art. Just as Hamlet’s psychology and the Mona Lisa’s smile become more enigmatic with each viewing, however many times you watch Mr Hurst’s shot, you can never know for sure.

4. The tragic hero. The World Cup final in Berlin in 2006 was the last game Zinedine Zidane ever played. He had already won the tournament once, spurring France to victory in 1998. After that, he was more than a footballer. In a country where Jean-Marie Le Pen of the National Front made it to the run-off in the next presidential election, Mr Zidane—the son of an Algerian warehouseman—became the face of a more tolerant France. Crowds in Paris chanted for him to be president.

The match in Berlin was heading for a penalty shoot-out; Mr Zidane, France’s captain, had already scored one in the game. With ten minutes to go, an Italian defender muttered something to him (about his mother, Mr Zidane alleged; only about his sister, the defender maintained). Mr Zidane headbutted the Italian in the chest. He was sent off. France lost the shoot-out.

This implosion was a tragedy in the purest sense. A tragedy, wrote Aristotle in the fourth century BC, depicts the fall of a great but flawed man, and hinges on a peripeteia, or sudden reversal, like the Italian defender’s slur. For Bernard-Henri Lévy, a French intellectual, the meltdown represented the “suicide of a demigod”—a tragic hero of whom too much has been demanded. Watch the scene closely, and there is indeed something oddly composed in Mr Zidane’s demeanour as, jogging away from his opponent, he hears, stops, and turns back to meet his fate.

5. A crack in everything. According to the Japanese aesthetic known as wabi-sabi, beauty is not perfect but flawed and incomplete. Leonard Cohen expressed the same thought in “Anthem”: “Forget your perfect offering/There is a crack in everything/That’s how the light gets in.” So, inadvertently, did Pelé, after he won the race with the Uruguayan goalkeeper.

Perhaps no one but Pelé would have done what he did next. He did nothing. His mind whirring faster than his feet, he did not touch the ball, as the keeper expected, but let it run on—hastily collecting it, after his coup de théâtre, on the other side of his opponent. Pelé shot towards the unguarded goal—but scuffed his kick and missed.

He still avenged his father and the Maracanazo. Brazil beat Uruguay and won the final, in which Pelé scored. Still, much later he said he had dreams in which, after that audacious moment of restraint, his aim was true: “It would have been so much more beautiful had it gone in.” He may be the greatest football artist of all time, but, about this, Pelé is wrong. The kink in the masterpiece is what makes it human.

Category: 1 - Long reads