That dear old oak in Georgia: the long aftermath of a lynching

That dear old oak in Georgia

The long afterlife of America’s only anti-Semitic lynching

The Economist | December 19th 2015 | MARIETTA

THE old man sat in the synagogue, jiggling his leg as he waited for the story’s grim climax. At last the lecture reached the night in August 1915 when Leo Frank was abducted by a gang, brought to this very neighbourhood, and hanged from a tree. When a list of the lynchers was projected onto the synagogue wall, the old man called out. What did the speaker know of the part played by the Burton brothers, Emmett and Luther? Only, came the reply, that the Burtons rode in the back of the car with Frank as, in his nightshirt and handcuffs, he was driven through the darkness to Marietta, and his death.

Emmett Burton was my father, the old man said; Luther was my uncle. He wanted everyone at the talk to know that, shortly after that episode, the Burton brothers enlisted in the American army and rode away in a boxcar to fight in the first world war. They were not just a pair of redneck extremists. They didn’t help to kill Frank because he was a Jew, as many then believed and still do. They did it for the little girl who had been murdered.

Reputedly the only anti-Semitic lynching in American history, Frank’s death shocked the country and traumatised its Jews. The tawdry, riveting affair combined skulduggery and shockingly public violence; depravity and courage; atavistic trauma and neuroses about modernity (for which, as they often do, Jews served as avatars). Alive and raw 100 years on, it has acquired new resonances and meanings. Now the case bears witness to the tenacity of the past-at once inescapable and intractable-and asks whether memory always illuminates the present, or rather sometimes poisons it. In the pain that still reverberates on its centenary, the story is a reminder that history can often be wrenchingly personal.

Atlanta, then and now

The case generally goes by Leo Frank’s name, but it began two years before his death, when, on April 26th 1913, Mary Phagan went to collect her pay at the National Pencil Company in Atlanta. In some ways, Georgia’s capital hasn’t changed all that much in the intervening century. Then, as now, its boosters peddled an optimistic version of the city as economically progressive and racially harmonious. Public transport, like the streetcar Mary rode into town, was at least as reliable as today’s. But in other respects the place was less recognisable. April 26th was Confederate Memorial Day, and Atlanta’s parade featured hundreds of real, limping veterans: the civil war’s wounds, physical and psychic, were still tender. Meanwhile the factories that powered the city’s resurgence ran partly on child labour.

Children such as Mary, who, at 13, had been employed to operate a machine that inserted erasers into the tips of pencils. That lunchtime she received her pay-$1.20-but never left the factory. In the small hours of the next morning she was found in the basement, her head gashed, her dress hitched up, a cord around her neck. Two mysterious notes lay nearby, purportedly written by her and incriminating “a long tall black negro”. “It’s too big a hole to put you in,” Mary’s mother, Fannie, cried at her funeral.

Sixty years later, the memory of “Little Mary”, as she instantly became, could bring her brother, Joshua Phagan, to tears. Mary Phagan Kean-Joshua’s granddaughter and the murdered girl’s great-niece-asked him about her once, in the 1970s. She looked a lot like his long-dead sibling, Joshua told her. But then he began to sob, and she never asked again. When she was born, though, he had requested that she be given his sister’s name. “My family”, Ms Phagan Kean says, “has struggled over this for 100 years.”

She spent much of her childhood abroad (her father was in the armed forces) and only learned the awful story when, aged 13 herself, a teacher asked whether she and her namesake were related. Today a room in her home in the apple-growing hills of north Georgia contains an archive-cum-shrine to Mary, holding the memorabilia and research she began to amass as a teenager. Ms Phagan Kean, a retired educationalist, tries to rebut what she sees as misconceptions about the case, insisting, for example, that Mary’s ten-cents-an-hour job was temporary and that the family was respectable. She curates her great-aunt’s memory in a more literal way, tending her grave in the old Confederate cemetery in Marietta, just north of Atlanta and hometown of the child’s extended family (the original Mary’s father died before she was born).

As children’s graves often are, Mary’s is cluttered with toys and miniature angels, at once mawkish and heartbreaking. The gravestone declares the dead girl’s “heroism” to be “an heirloom, than which there is nothing more precious among the old red hills of Georgia”. That is a reference to the theory that she died resisting sexual assault-just as the South itself, many southerners believed, had nobly resisted violation by the north. The botched investigation failed to confirm that hypothesis, along with other key facts. Atlanta’s police were bumbling, brutal and corruptly entwined with its newspapers, which, following William Randolph Hearst’s purchase of the Atlanta Georgian, were themselves embroiled in a reckless circulation war.

Of the many suspects the police detained, amid a frenzy of tip-offs and slanders, the man charged-because of his allegedly shifty demeanour, as well as groupthink, stubbornness and latent rivalries among police and lawyers-was Leo Frank. Then aged 29, Frank was born in Texas but grew up in New York and studied at Cornell University. He was the pencil factory’s superintendent (his uncle Moses was a shareholder), and, having dispensed Mary’s pay, was the last person to acknowledge seeing her alive. He was also a Jew. “Police Have the Strangler” screeched the Georgian’s front page after his arrest.

Two slugs of evidence helped secure his conviction in a cramped, baking Atlanta courtroom. A gaggle of young women testified that he had previously harassed Mary or themselves. More damning still was Jim Conley, a hard-drinking, heavily indebted factory sweeper with a police record as long as his broom. Lionised as the “ebony chevalier of crime”, Conley claimed to have stood guard while Frank conducted assignations in his office. As Steve Oney relates in “And The Dead Shall Rise”, a superb history of the case, after Conley alleged that his boss had a penchant for oral sex, the judge cleared female spectators from the courtroom. According to Conley, Frank “wanted to be with the little girl” and struck her when she refused; Conley had written the strange notes at Frank’s dictation, and had helped move Mary’s body to the basement.

As the best lies are, his account was rich with idiosyncratic details: of clothes and drinks and dialogue. By contrast, Frank’s statement was nerdy and rambling. The prosecutor timed his summation so that his final word-“Guilty!”-punctuated the chimes of a church clock. The jury obliged, the judge sentenced Frank to death and Atlanta rejoiced.

Frank wasn’t in court for the verdict: everyone agreed the risk of mob violence, should he be acquitted, was too high. His absence informed claims that the whole trial was discredited by prejudice. Certainly both sides dealt in noxious racial stereotypes, sexual and otherwise-of Jews but, even more, of blacks. The defence called Conley “a plain, beastly, drunken, filthy, lying nigger”, arguing that to take his word over a white man’s would be disgraceful; the prosecution relied on the perception that he was too simple to have invented his tale.

Ms Phagan Kean believes Frank was guilty, and that the trial itself was not anti-Semitic. Reports that, as the jury deliberated, crowds chanted “Hang the Jew or we’ll hang you!” are, she points out, apocryphal. But she does not deny the tornado of prejudice that engulfed Frank afterwards. Eminent northern Jews mobilised for his freedom, comparing his predicament to the Dreyfus affair in France. The ferocious response in Georgia was led by Tom Watson, a former congressman and Populist vice-presidential candidate, by then the demagogic publisher of the Jeffersonian. His coverage blended ancient anti-Semitic tropes of Jewish predation and avarice with the resentment of carpet-bagging Yankees to which, as a northern industrialist, Frank was equally vulnerable.

J’accuse, y’all

It is an ugly story, but it has its heroes. William Smith, an enlightened lawyer who represented Conley, was one. Analysing the murder-scene notes after the trial, Smith became sure that his own client was their author and had therefore committed the crime-and wrecked his own career by saying so. On his deathbed Smith again affirmed Frank’s innocence. Another was John Slaton, Georgia’s governor and Frank’s last hope after other legal remedies failed. Slaton re-examined the evidence during his final days in office. “I would be a murderer if I allowed that man to hang,” he concluded as he commuted the sentence to life imprisonment. A mob promptly besieged his mansion; Slaton was burned in effigy and reviled as “King of the Jews”. Rumours of secret financial inducements-of “Unlimited Money and Invisible Power”, in Watson’s words-swirled around the case, as, more quietly, they still do.

He couldn’t save Frank. Watson demanded his lynching; with unusual premeditation, a vengeful group from Marietta, drawn from families that were (and in many cases, remain) wealthy and well-connected, vowed to accomplish it. Among them were a judge, a sheriff, a mayor, incumbent and former state legislators and a former governor of Georgia. Naturally, they enlisted less prominent men to do most of the dirty work. The recruits included Emmett Burton and his brother Luther.

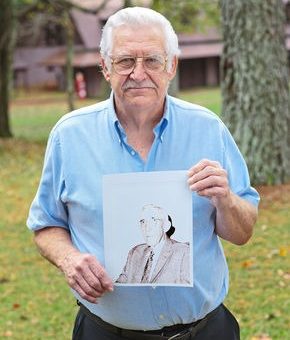

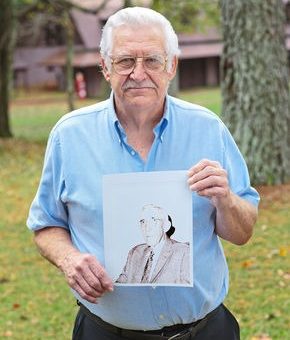

Those two were not, maintains Emmett Burton’s son (also called Emmett), “two crazy men after a Yankee Jew”. If they had been motivated by prejudice, he and others ask, why didn’t they settle on Conley, the black man? They thought Slaton, who was a partner in the firm of one of Frank’s lawyers, was chasing Jewish business. “He was convicted and his sentence was to hang,” says the surviving Emmett Burton, still a resident of Marietta and now the closest living relative of anyone involved. “What’s the difference in who hung him?” His father’s role was “nothing anybody bragged about”, he says, but nor is it a source of shame. “They just wanted to give that little girl justice.”

Yet along with their perspective on the killings, in private as at the synagogue, Mr Burton urgently wants to relay his forebears’ wider personalities and deeds: to insist, in other words, that a person’s life should not be reckoned by one dark night. He tells a funny story about Emmett senior resisting his regulation buzz-cut after he joined the army and ending up with a stripy bonce; he has the record of his father’s discharge after the first world war, which describes his character as “excellent”. The elder Emmett was a farmer and long-serving police officer, who, says his son, distributed silver dollars to children at Christmas: “Daddy was well thought of.” For his part, Uncle Luther was a champion chequers player; he ran a coal-yard and, during the Depression, gave coal to the poor. He was known as “dollar-bill Burton” for his generosity.

Mr Burton has bills of sale that show his father traded with Jews, and he has photographs. Just as old pictures help to resurrect the victims in the case-Little Mary impishly pretty, Frank pale and fragile, both of them tragically unaware of their impending fates-so do photos of the vigilantes. There is Emmett senior, a lean young man in farm overalls; there he is again, older and in police uniform. To his son, he was not a villain but an upstanding citizen, and a parent. “My father”, Mr Burton says, “was not a low-life drunken monster.”

Just like the old days

On the night of August 16th 1915 the lynching party drove to the state prison at Milledgeville, cut the phone lines, easily subdued the staff-the ringleaders seem to have leaned on prison authorities-and handcuffed and abducted Frank. He sat between Emmett and Luther in the back of one of the convoy’s cars. Local legend has it that the brothers told Frank he would be spared if he confessed. (“That’s Hollywood,” Mr Burton comments dismissively. “Why would they say that?”) Near dawn, on the outskirts of Marietta at a place called Frey’s Gin, named for the former sheriff who owned the land, the lynchers looped a rope around the bough of an oak tree and perched Frank on a table. A fellow prisoner had tried to cut his throat, so his last words may have been hoarse: “I think more of my wife and my mother than I do of my own life.” It wasn’t a long drop and he didn’t die quickly.

A large crowd soon gathered: lynchings, like other forms of terrorism, were above all public spectacles. After it was cut down, Frank’s body had to be wrestled away from the mob, like some Southern Gothic version of a scene from the “Iliad”. Pieces of tree and rope-though not, as in some instances, pieces of the victim himself-were taken as souvenirs. Thousands more people viewed the corpse at the undertaker’s in Atlanta, just as thousands had filed past Mary’s. “The Wages of Sin is Death,” crowed Watson in the Jeffersonian. “Semper Idem” reads the gnomic Latin inscription on Frank’s headstone in New York: “Always the same”.

Today the lynching site is a patch of noisy scrubland in the shadow of an interstate flyover. Unlike the nearby Big Chicken, a giant mechanical rooster that nests on a fast-food restaurant and is a Marietta landmark, the place is unheralded and overlooked, as well as overgrown. The trees themselves are long gone (though for a while part of Frank’s bloodied nightshirt was displayed at a bar up the road). So are the plaques affixed by Rabbi Steven Lebow to the side of an adjacent office building, since demolished. Still, for the past 20 years, on the anniversary of the lynching Mr Lebow has said kaddish, the Jewish prayer of mourning, for Frank on this spot; in recent years he has said it for Mary, too. He keeps the plaques in his room at Marietta’s Kol Emeth synagogue.

Mr Lebow grew up in Florida and moved to Marietta in 1986, peripherally aware of the Frank affair from studying and teaching Jewish history. His interest was galvanised two years later by the broadcast of a mini-series about it, starring Jack Lemmon as Slaton. He realised that he was passing the lynching site every day on his way to the synagogue. After he put up the plaques, he would occasionally trim the foliage around them in the middle of the night. Sometimes he walks his dog here. “A rabbi”, says Mr Lebow, “is a professional rememberer.” And, in Frank’s case, for a long time everyone else wanted to forget.

That included America’s Jews. Initially there was uproar-among Jews who thought such bloodletting belonged in old Europe, and those gentile Americans who agreed. From a modern perspective, the killers’ impunity was even more shocking than the crime. Many photographs were taken, which soon circulated as postcards, as was customary. None of the smiling faces around the dangling corpse is covered. Yet no one was punished-not surprisingly, since the investigation was overseen by one of the conspirators, and the grand jury convened to consider the case was stuffed with them. On the contrary, some of them benefited. Watson became a senator; the circulation of his Jeffersonian rocketed. The prosecutor at the trial became governor of Georgia. The broader cause of American racism was fatefully buoyed as well. Several of the participants joined the posse which, three months later, ascended Stone Mountain, just outside Atlanta, to burn a huge cross, marking the rebirth, after a 45-year hiatus, of the Ku Klux Klan. Luther Burton later signed up.

But for Jews in Marietta and Atlanta, the legacy was a strangulating compound of fear and shame. Jewish businesses were vandalised and some Jews harassed. Many fled, their hopes of amicable integration undone. Chuck Marcus, a great-nephew of Lucille Frank, Leo’s widow, says his father Alan, a child in 1915, remembered leaving Atlanta in a wagon in the middle of the night; the family’s lives were marred for ever, Mr Marcus says. He himself knew nothing about the calamity until Lucille died in 1957 (she mostly stayed in Atlanta, working at the glove counter of a department store, where her customers included wives and daughters of her husband’s killers). Forever wary of unwanted attention, Lucille asked to be cremated. For months Alan Marcus kept her ashes in the boot of his car; eventually, in secret, he and his brother buried them between her parents’ gravestones.

One in six million

Just as Atlanta’s Jews preferred not to talk about Frank, so, for different reasons, did the lynchers. The case receded from public consciousness, but it didn’t die. In 1982 Alonzo Mann-then 83, but in 1913 an office boy at the National Pencil Company-came forward to say that, on the day of the murder, he had seen Conley carrying Mary’s body, in circumstances that contradicted the sweeper’s testimony. Conley had threatened him, Mann said, and his parents had enjoined him not to tell anyone. That set off a push for a posthumous pardon. Even then, some elderly Jews were opposed to the effort, for fear of raising old demons. Evidently those nerves were justified. Roy Barnes-then a political ally of Georgia’s governor, a job he later did himself-says that influential people lobbied against the initiative. Anti-Semitism infected the debate.

In 1986 a pardon was granted, on the basis not of Frank’s innocence but that the state had failed to protect him. Then, in 2000, a list of the lynchers, originally compiled by Ms Phagan Kean, found its way onto the internet. Several such rosters were put together over the years-characteristically for a case in which everything is doubled. It has two murders, two Leo Franks (innocent and perverted), two Atlantas (bustling and barbaric). But this was the first to be published. Among those who learned only in the 21st century that their family was complicit was Governor Barnes’s wife, whose grandfather was on the lists. She was ashamed.

Still it isn’t over. At a moving memorial service in August, Mr Lebow and assorted Georgian judges called for Frank to be fully and finally exonerated by the state. “It is not possible to make the future good”, the rabbi told what, these days, is Marietta’s thriving Jewish community, “unless we are willing to make the past right.” Over the summer a roadside billboard proclaimed Frank’s innocence. Once again, there are dissenters.

Mr Lebow and Ms Phagan Kean, Little Mary’s great-niece, have clashed in the past. Why, she asks, is the rabbi so interested in a case to which he has no direct connection? And indeed there is something quixotic about this focus on a 100-year-old incident when so much else has befallen the world’s Jews and, for that matter, Georgia. Altogether 22 people were lynched in the state in 1915, including John Riggins-a black man, like all the mobs’ other victims-who was killed on the same day as Frank. Georgia lagged behind only Mississippi in that abhorrent pursuit. For all the guff about progress, dozens of blacks were massacred in Atlanta itself during a racist pogrom in 1906, just a few years before the Phagan-Frank saga began.

The rabbi thinks Frank’s fate emblematic of all these injustices, from the atrocities of the Jim Crow era to contemporary police violence. That view is endorsed by civil-rights leaders such as John Lewis, a congressman whose skull was fractured on the bridge in Selma in 1965, and who agrees that “racism and anti-Semitism are one and the same”. Mr Lebow himself has fought other battles. He first got involved in civil-rights issues after the county commission passed a homophobic resolution in the 1990s.

But he acknowledges that his devotion to Frank’s cause has a psychological component, too. He has no extended family: many of his relatives died in the Holocaust, leaving the American branch with only another set of painfully inadequate black-and-white photographs. All that wider suffering is not a contradiction of his mission, he reasons, but an explanation. “This is my one small corner of the world that I can attempt to put right,” the rabbi says. “I can’t do anything about the 6m, but this one has a name and a face I know.”

Leo Frank, the musical

Gruesome as their deaths were, Mary Phagan and Leo Frank have inspired many artists. Besides the television series and other screen adaptations, there are the songs. Fiddlin’ John Carson, balladeer of the poor, rural whites who swelled Atlanta’s population at the turn of the 20th century, wrote several. In the lyrics of the best-known, Frank “laughed and said, Little Mary,/You’ve met your fatal doom”. Carson sang that on the steps of the state capitol as the governor weighed the condemned man’s life. Another of his ditties celebrated the “Dear Old Oak in Georgia” from which Frank was hanged.

Then there is “Parade”, a musical that premiered on Broadway in 1998 and was later a hit in London. In November students at Kennesaw State University revived it for one night in Marietta, part of a series of centennial events organised by the university and the Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History. “Parade” emphasises Georgia’s lingering Confederate sentiment and Frank’s incongruous northernness: he cannot bear Atlanta’s “magnolia trees and endless sunshine”. Alfred Uhry, the librettist, is the great-nephew of the National Pencil Company’s biggest shareholder. As a child he knew Lucille Frank, he recalls, but when Leo was mentioned older family members would leave the room. The theatre stands on the square where, 100 years ago, jubilant townsfolk gathered after the lynching.

As Mr Oney, the author, puts it, alone among Americans southerners are constantly stumbling over partly open graves, endlessly confronting the sins of previous generations. Some would prefer this particular trauma to be irrevocably interred. “The Phagan family”, insists Ms Phagan Kean, “wants this to die.” She was in the theatre for “Parade” and was distressed by its portrayals of Little Mary as flirtatious and her mother Fannie as anti-Semitic. “They don’t realise how much pain they cause,” Ms Phagan Kean says. She rebuffs the overtures of far-right groups who try to exploit her great-aunt’s death: the Klan once marched to the cemetery (some of the lynchers are buried there too), and on the internet Frank is a pin-up for white supremacists. Equally, though, she passionately opposes his exoneration. Somehow she believes that those advocating it dishonour Mary’s memory. If the rabbi gets his way, she says, she will erect a marker declaring Frank the murderer: “I’m not going to stop.”

A century on, conclusive proof is impossible. What is clear is that the trial was unfair-by the standards of its own time, let alone today’s. The prosecution suppressed evidence that favoured Frank; prejudicial testimony was admitted; several damning witnesses later recanted. Conley-who did ten months on a chain gang as an accessory, but was soon back inside-lied incessantly. At first he claimed to be illiterate, admitting he wrote the notes only after his handwriting was identified; his story changed drastically under police tutelage. Almost certainly he killed Mary himself, realised that someone would have to swing, and saw a way for that to be Frank. But probably only he, Frank and Mary could ever have said for sure.

Some things will never see the light of day. “All I know”, says Mr Burton, “is that it didn’t happen like they’re saying.” Coincidentally he is an expert on vintage cars-for 35 years he supplied vehicles for films-and he is convinced his father, uncle and the rest couldn’t have got to Milledgeville and back in the way conventional accounts of that night describe. He believes the conspiracy was even wider, and blame more diffuse, than it appears. But he knows it is too late for further resolution. “There’s nothing that can be done now,” Mr Burton says. “It’s all been done.” Most of all, he “would like for it never to be discussed again by anybody.”

Frank was not talked about in the Burton household. But, in a tangible way, he was always there, and still is. In the dresser in the master bedroom there was a drawer that was always locked. Inside the drawer there was a box, also locked. In the box, Mr Burton says, were the handcuffs his father put on Frank’s wrists at the prison and took off him when he was dead. He still has the handcuffs, though he declines to produce them. “Nobody”, he says, “will ever lay their eyes on them.”

Category: 1 - Long reads